St Gallen Symposium Global Essay Competition 2024

The Politics of a Post-Truth Era & The Promise of Democratic-Communicative Knowledge Democracy - by Zihan Xuan

Introduction

“The world is changing. Truth is vanishing,” whispers the ever-mysterious arms dealer sleekly played by British actress Vanessa Kirby. “War is coming.”

However cryptic these warnings appear in the latest installation of the Mission Impossible franchise, they seem oddly resonant in our contemporary era. In many societies, truth has evolved to become a rare and endangered commodity. Barely two centuries after the Enlightenment strengthened our collective faith in the human endeavour of truth-seeking, the very notion of an objective and universal capital-T Truth now inspires apathetic distrust at best and attracts empty ridicule at worst.

A constellation of factors explains why the availability of truth is in short supply today. In liberal democracies, heightened political polarisation and populist resentment towards the governing elite have engendered a seemingly intractable bifurcation of normative worldviews. In authoritarian-leaning societies, it is a Sisyphean feat to distinguish between truth, myth, and pure fabrication, which are all inextricably entangled within a web of propaganda and vested interests. To compound the deficit in truth, the exponential proliferation of social media and AI algorithms in an unfolding ‘infocalypse’ ensconces us in a cocoon of warped realities and echo chambers.

Given the scarcity of truth, this essay will present the following argument: while postmodernist thought fuels justifiable suspicion of capital-T Truth as grands récits, the pursuit of truth remains relevant from both normative and utilitarian angles, given its nature as an instrument of social justice and a mechanism for consensus-building. Reconciling this theoretical tension and building on existing political theory, this essay then proposes a deliberative-communicative knowledge democracy (DCKD) as a novel political structure, which juggles the Janus-faced nature of T/truth and secures better governance outcomes, through a combination of intersubjective deliberation and exploratory communication.

Towards the Postmodern Decay of Truth

To begin with, the scepticism towards capital-T Truth does not come without a kernel of truth. Taking postmodernism as our departure point, a post-World War II generation of theorists across philosophy, psychology, linguistics, and cultural theory championed a progressive resistance towards grand narratives, and embraced the relativity of truth across temporal and geographical boundaries. Beyond its theoretical appeal in an era of moral uncertainty, the revolutionary implications of postmodernist thought continue to be widely recognised. Consider, for example, how postmodernism enables the ‘subaltern’1 to assert their independent voice, by imbuing them with the legitimacy to deconstruct the myth of colonialism and the (pseudo-)scientific basis of (self-proclaimed) racial superiority. In so doing, postcolonial theory provides an avenue for historically oppressed communities to reject the “totalising systems and manifestations of modern thought”, and strive for true emancipation amidst the lasting vestiges of imperialism (Salhi, 2020: ix). Along similar trajectories, postmodernism surfaces in the philosophy of science as Thomas Kuhn’s theory of paradigm shifts, underscoring the extra-rational role of the ‘leap of faith’ in triggering scientific revolutions, and cautioning us against blind, unquestioning adherence to scientific discoveries (Kuhn, 1962).

Taken together, postmodernism welcomes the loss of capital-T Truth as a source of intellectual and political liberation, while interrogating overarching and self-evident truths as convenient ideological devices. Extending this radical line of criticism and citing political commentary on the vagaries of US Presidential debates (Kelly, 2023), even if truth is in short supply, is there genuinely a scarcity of concern if there is no demand for truth in the first place?

1 The term ‘subaltern’ was coined by Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci and popularised by Indian literary critic Gayatri Chakrovorty Spivak (Spivak, 1988). In a postcolonial context, it refers to marginalized social classes and the colonised ‘Other’, who are often subjected to silence and subjugation by colonial powers.

Rescuing Truth from its Ideological Captors

However, before we prematurely toast to the seductive downfall of Truth, a reality check is in order, to avoid the weaponisation of postmodernism for insidious ends. In particular, since truth serves important functions as an instrument of social justice and a mechanism for consensus-building, its scarcity poses serious threats to collective social progress.

First, the pursuit of truth is a critical ingredient in the fight for social justice. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, American political theorist Hannah Arendt keenly observed that “[t]he ideal subject of totalitarian rule is [...] people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction […] no longer exist” (Arendt, 1951). While her work primarily targeted 20th-century political regimes, it also demonstrated the importance of an open and contested intellectual environment, with truth as its guardrail, a critical citizenry as its custodian, and social justice as its raison d'etre. Consider an extreme but particularly pertinent topic today. If truth is but a mirage, what defence then can we marshal against the seeds of hate and suspicion sown by denialism, for example of the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide (Kahn- Harris, 2018)? To victims of these atrocities, subverting such established truths can readily devolve into a rejection of the immediate materiality of their lived experiences, while weakening our imperative to hold individuals and institutions accountable to fundamental moral and political standards. In situations where the truth can be a matter of life and death, our indifference attests to our complicity in the perpetuation of both physical and epistemic violence and constitutes a travesty of justice.

Furthermore, truth fulfils an integral role in providing a common frame of reference that orients our public discourse. Conversely, the dismissal of truth provides an indefensible carte blanche for ill-intentioned agents to poison not just our perception of reality, but also our very ability to resolve our natural disagreements, leading to deeply troubling societal outcomes. If individual citizens are free to subscribe to so-called “alternative facts'', it is little wonder that we are forced to confront (and subsequently fail to dispel) outright conspiracies, ranging from the viciousness of Covid-19 vaccines to the harmless hoax of climate change. In the United States, a simple majority of adults deem misinformation and disinformation to exert a significant impact on their confidence in government (68%) and in each other (54%) (Pew Research Centre, 2019). In the United Kingdom, a political culture of exaggeration and deceit, which arguably served as a cornerstone of the pro-Brexit campaign, has profoundly undermined the “commitment to truth-telling and a shared acceptance of facts, however differently they may be interpreted” (Hutton, 2021).

A broader post-truth paradigm unites the common threads across the world’s oldest democracies above: by converting epistemic contentions into motivational shouting matches (Hannon, 2023), we breed an impenetrable sense of entitlement that makes us impervious to constructive and fact-based deliberation. Therefore, where truth is valourised as the foundation of public discourse, we ignore its gradual extinction at our own peril.

Deliberative-Communicative Knowledge Democracy

In response to the scarcity of truth, devising a sensible solution is, perhaps counter-intuitively, not about thriving with less T/truth or striving for more T/truth, which is a binary choice structure that ignores the nuances of the divide. Instead, a more appropriate response must be framed in terms of how society can straddle both the continued normative and utilitarian relevance of T/truth, as well as the postmodern desire to accommodate competing viewpoints in the spirit of egalitarianism. Especially for intangible social resources and public goods such as truth, it is important to question, if not transcend, the market logic of demand and supply implicit in conventional understandings of scarcity. The deeper and more meaningful challenge for society, and what this paper aims to achieve, is to distil what the perceived scarcity of truth reveals about our conceptualisation of the varied facets of T/truth (addressed above), and to advance an effective response that can capture the different ways in which we value T/truth and its pursuit (addressed below).

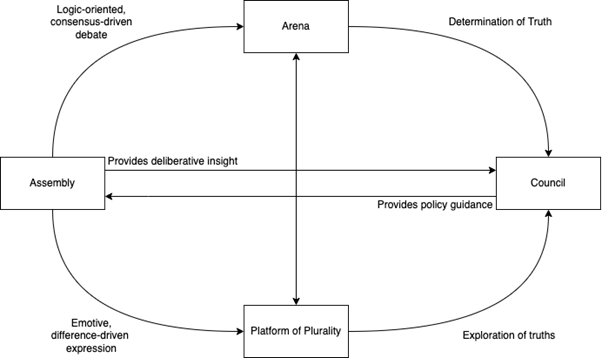

The core solution proposed by this paper is a novel political configuration based on a unique blend of deliberative democracy (as proposed by German philosopher Jürgen Habermas) and communicative democracy (as proposed by American political theorist Iris Marion Young). Figure 1 offers a visual representation of what this paper terms as the deliberative-communicative knowledge democracy.

Figure 1: Deliberative-Communicative Knowledge Democracy

The overarching structure of the DCKD is defined by a two-way, mutually informed relationship between the main organs of the ‘Assembly’ and the ‘Council’: while the former provides deliberative insight to the latter, the latter synthesises such insight to provide policy guidance to the former. There are two channels that mediate the above relationship: the ‘Arena’, which fosters logic-oriented, consensus- driven debate, and the ‘Platform of Plurality’, which empowers emotive, difference-driven expression. In so doing, the Arena and Platform of Plurality serve as auxiliary decision-making tools that help society wrestle with the complexities of our pursuit of T/truth.

The Arena & Deliberative Democracy

The main objective of the Arena is to provide a space for deliberative democracy, whose distinctiveness rests on the intersubjective interpretation of popular sovereignty (Scudder, 2021). Deliberative democracies encourage the process of mutual justification among a diverse group of citizens to forge “symbolically mediated and materially relevant arrangements” (Kulha et al, 2021; Susen, 2018), which are then conveyed to the Council as policy recommendations. Public discussions are grounded in logic and consensus-building, such that individuals exercise their mental faculties and retain the open-minded willingness to change their views if better reasons are articulated by their fellow citizens (Habermas, 2018: 874). In the Arena, the (albeit elusive) ideal of an empirically robust truth remains the anchor that sharpens the interactions and intersections between competing cognitive perspectives.

Notably, such deliberative democracy has promising truth-tracking potential, in the sense that the combination of open and free debate, equal status of citizens, and critical thinking in the Arena provides the “structural and procedural conditions'' that guide us towards better governance outcomes (Chambers, 2021), such as instituting a stronger pushback against fake news, counteracting polarisation, and enhancing public trust (The Hague Academy, 2022). To overcome epistemological nihilism and improve decision-making, the Arena protects the sanctity of Truth through intersubjective deliberation, rather than heavy-handed regulation or arbitrary censorship.

The Platform of Plurality & Communicative Democracy

In contrast, the Platform of Plurality serves as a check and balance against the absolute power of the Arena. Whereas deliberation tends to assume unity and consensus, and rely on a primarily argumentative means of reasoning, it may preclude the inclusive participation of individual citizens with a preference for alternative modes of expression, stifle the articulation of particularities by marginalised groups, and neglect the “phenomenology of recognition among the subjects of the discourse” (de Lima & Sobottka, 2020: 12). Consequently, the sole reliance on deliberative democracy, which is underpinned by institutional rules and practices derived from “Greek and Roman political traditions adapted by bourgeoise revolutionaries” (Martínez-Bascuñán, 2016), risks the reproduction of structural inequalities and power asymmetries across varying axes of identity, including but not limited to race, gender, and class.

In the spirit of postmodernism, the Platform of Plurality aims to empower – rather than assimilate – different speaking styles and reasoning modes, offering the resulting multiplicity of truths as a political resource for the Council’s consideration. Therefore, communicative democracy facilitates our engagement with our own partiality and situatedness in the social world, and elevates narratives and life experiences to a level playing field (Young, 1996). While modern-day instantiations of communicative democracy are relatively under-developed, albeit with micro-applications in educational settings that mitigate latent power differentials and improve pedagogical outcomes (Weasal, 2016), the DCKD aspires to further the salience of the model to harness the postmodern promise of true inclusion.

Overall, the DCKD leverages the complementary setup of the Arena and Platform of Plurality to operationalise Habermas’ deliberative democracy and Young’s communicative democracy, enabling the Council’s policy guidance to be truly reflective of and responsive to the Assembly’s diverse voices and perspectives. Taken together, the DCKD provides a practical, innovative, and holistic way to reform and reimagine our existing models of political governance to engage with the multi-faceted nature of T/truth.

Conclusion

In sum, this essay has served to reconcile the two opposing inclinations that arise due to the scarcity of T/truth: either to celebrate the decline of capital-T Truth as a grand narrative and champion postmodern liberation in a world where we live our own truths, or to defend the continued relevance of truth as an instrument of social justice and a mechanism for consensus-building. In light of the complexities of our quest for T/truth and the resolve to balance both competing perspectives of T/truth, this essay has proposed the establishment of a deliberative-communicative knowledge democracy, and demonstrated how the political organs and decision-making tools of the DCKD can create better governance outcomes through intersubjective deliberation and exploratory communication. While future research is required to adapt the concept to non-ideal circumstances, the DCKD furnishes the policymakers of today with a more well-informed model to design the political systems of tomorrow.

Reference List / Bibliography / Sources:

Arendt, H. (1951) The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York, USA: Schocken Books.

Chambers, S. (2020) ‘Truth, Deliberative Democracy, and the Virtues of Accuracy: Is Fake News Destroying the Public Sphere?’, Political Studies, 69(1), pp. 147–163.

de Lima, F.J.G. and Sobottka, E.A. (2020) ‘Young’s communicative democracy as a complement to Habermas’ deliberative democracy’, Educação e Pesquisa, 46.

Habermas, J. (2018) ‘Interview with Jürgen Habermas ’, in A. Bächtiger et al. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 871–882.

Hannon, M. (2023) ‘The Politics of Post-Truth’, Critical Review, 35(1–2), pp. 40–62.

Hutton, W. (2021) The case for Brexit was built on lies. Five years later, deceit is routine in our politics. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jun/27/case-for-brexit-built-on-lies-five- years-later-deceit-is-routine-in-our-politics.

Kahn-Harris, K. (2018) Denialism: what drives people to reject the truth. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/aug/03/denialism-what-drives-people-to-reject-the-truth.

Kelly, D. (2023) OPINION | DANA KELLEY: Truth serum needed. Available at: https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/sep/29/truth-serum-needed/.

Kuhn, T. (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Kulha, K. et al. (2021) ‘For the Sake of the Future: Can Democratic Deliberation Help Thinking and Caring about Future Generations?’, Sustainability, 13(10).

Martínez-Bascuñán , M. (2016) ‘Misgivings on Deliberative Democracy: Revisiting the Deliberative Framework’, World Political Science, 12(2), pp. 195–218.

Pew Research Center (2019) Americans’ struggles with truth, accuracy and accountability. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2019/07/22/americans-struggles-with-truth-accuracy-and- accountability/.

Salhi, L. (ed.) (2020) Postmodern and Postcolonial Intersections. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Scudder, M.F. (2021) Deliberative Democracy, More than Deliberation, 71(1), pp. 238–255.

Spivak, G. (1988) ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, in C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (eds.) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. London, UK: Macmillan.

Susen, S. and Forchtner, B. (2018) ‘Jürgen Habermas: Between Democratic Deliberation and Deliberative Democracy’, in R. Wodak (ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Language and Politics. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, pp. 43–66.

The Hague Academy (2022) Deliberative Democracy in Action. Available at: https://thehagueacademy.com/news/a-quick-guide-to-deliberative-democracy/.

Weasal, L. (2016) ‘From Deliberative Democracy to Communicative Democracy in the Classroom’,

Democracy & Education, 25(1).

Young, I.M. (1996) ‘Communication and the Other: Beyond Deliberative Democracy’, in S. Benhabib (ed.) Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political. New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press, pp. 120–135.

Word Count (essay text only): (2100/2100)