Max Han, an MSc student at the ECI brings a unique perspective to Oxford — one grounded in grassroots organising and frontline advocacy across Southeast Asia. For the past three years, he has worked alongside diplomats, UN agencies, and civil society groups to shape what could become the region’s first Environmental Rights Declaration.

Here Max reflects on the urgency of defending environmental and human rights in the face of political risk, and the importance of bridging community voices with institutional decision-making.

I’d always remember the first consultation I held with an environmental human rights defender from the Philippines. She looked me in the eye and said, “I’ve already lost four friends this year. Two were arrested. One was imprisoned. One disappeared.”

She paused and added, “But we have no choice but to fight back for our lands. If we don’t speak up, who will?”

In Southeast Asia, defending the environment can be risky. Protecting land, flora and fauna often means standing up to powerful interests, navigating shrinking civic space, and sometimes, putting your life on the line. As my colleague Lia Mai Torres of the Asia Pacific Network of Environmental Defenders (APNED) shares, “We have enforced disappearances. We have bombings in our communities and militarization. We have killings of farmers and Indigenous people just for working on their land.”

These are not isolated tragedies, but rather symptoms of a deeper crisis. In our region, the climate crisis is not just environmental. It is political. It is personal. And it is a human rights crisis.

Over the past three years, I’ve been part of a working group under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) trying to tackle these environmental rights issues with policy. Our group comprises of diplomats, UN bodies, and civil society, and we have been collectively drafting what could become Southeast Asia’s first Environmental Rights Declaration. If adopted, this declaration would set a regional standard for environmental and human rights, carry political weight across administrations, and potentially influence national policies. More than anything, it would mark a historic step toward recognising a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a fundamental human right for the 690 million people in Southeast Asia – roughly 9% of the world’s population!

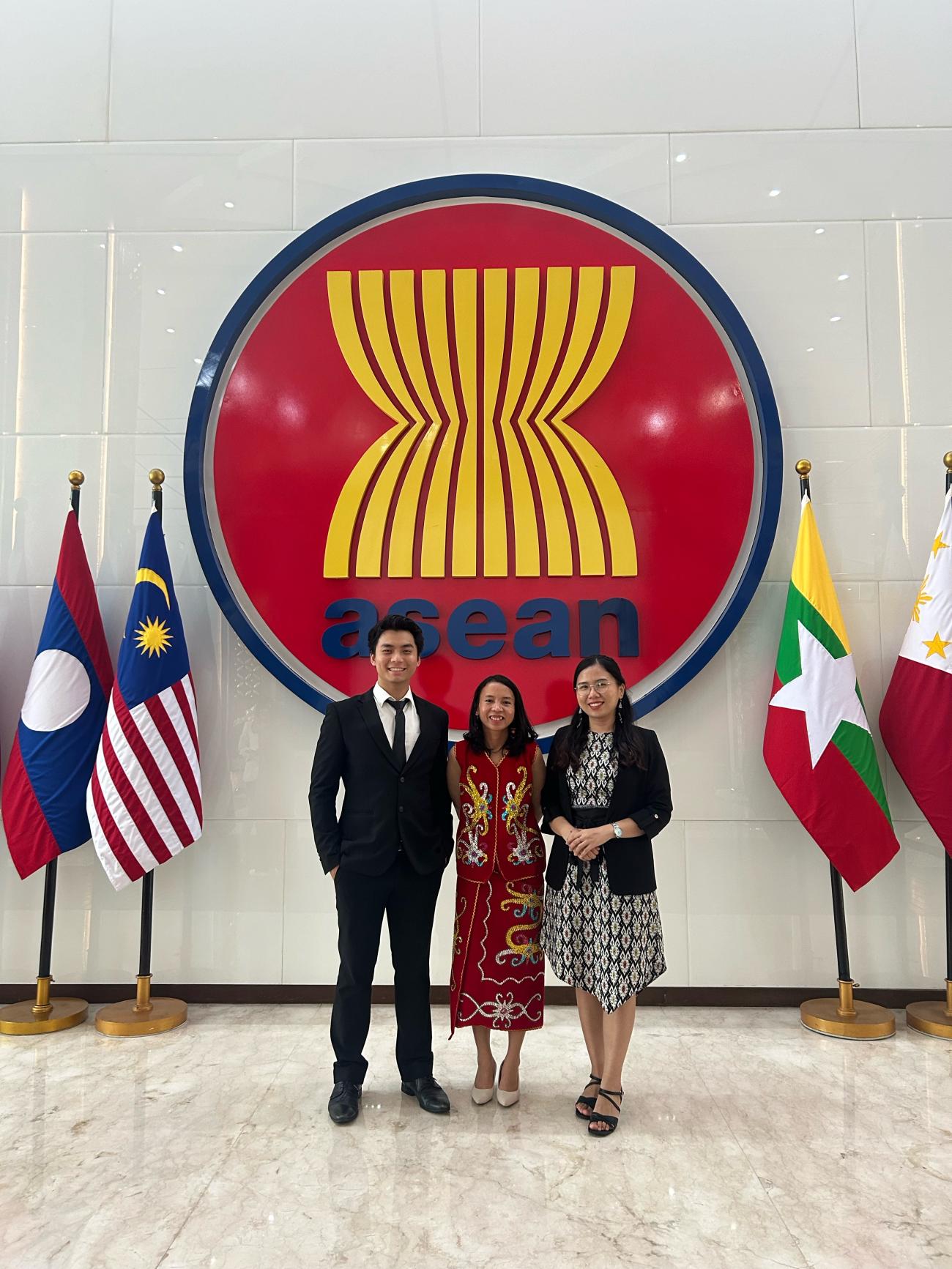

Max Han, with Sumarni Laman, and Fithriyyah from the ASEAN Youth Forum at the ASEAN Headquarters in Jakarta, Indonesia

The declaration seeks to institutionalize both substantive rights (access to clean air, water, and a safe climate) and procedural rights (access to environmental information, public participation, and justice). We have also been lobbying for the recognition and protection for environmental human rights defenders (EHRDs): Indigenous leaders, youth activists, journalists, and lawyers who risk their lives to protect the environment and their communities. By protecting people who are protecting the environment, you are, in effect, protecting the environment.

However, the process has been fraught with challenges. What began as a bold, 17-page legal framework was gradually reduced to a non-binding declaration, now undergoing ministerial review in the hopes of being adopted. Key terms like “Indigenous peoples” and “Environmental Human Rights Defenders (EHRDs)” were bracketed and now left in a state of precarity. While public consultations were technically included, they were underfunded and highly decentralised. Many of us in civil society took it upon ourselves to translate the draft into local languages, organise dialogues across the region, and collect feedback with limited time and support.

Yet, I still believe this declaration matters. Even in its weakened form, it sets a political precedent. It gives us a benchmark to hold governments accountable. But more importantly, its process reminds me of a deeper truth: that laws and policies alone aren’t enough.

What we need is better bridge-building — between local communities and policymakers, between traditional knowledge and formal institutions, between the frontline and the negotiating table. During the drafting process, it was civil society, youth, and indigenous leaders who carried this declaration into communities and brought those critical voices back. That kind of bridge work is essential, and yet it is too often under-recognised, under-resourced, and under-represented in formal decision-making spaces.

This bridge-building is exactly what I am hoping to hone in on at Oxford. With a background of grassroots organising, I’ve felt disoriented at times within elite academic spaces. But I chose the MSc in Environmental Change and Management because I believe real transformation requires both lived experience and strategic systems thinking. At the School of Geography, I’m learning to analyse policy frameworks, map governance structures, and navigate the language of institutions while also challenging this institution’s biases, grappling with the colonial roots of geography, and grounding myself in the voices at the margins of the discipline. These are skills I hope to bring into my work in Southeast Asia to help strengthen the bridges we so urgently need.

My hope is that this process will help me and others build regenerative systems that don’t sacrifice the most vulnerable. That we can replace extractive development with community-led resilience. That Southeast Asia can rise as a region of bold rights-based environmental governance, not just crisis.

And if we are to build the future we need, we must start by building better bridges — between the dreaming spires of Oxford and lived realities, between people and policy, between power and justice, and across the fault lines of a region that is ready to rise.

About Max

Max Han is the co-founder of Youths United for Earth (YUFE), a nonprofit mobilising youth for environmental action through storytelling, advocacy, and campaigning, and represents the ASEAN Youth Forum on the ASEAN Environmental Rights Working Group. He is currently pursuing a Master of Science in Environmental Change and Management as a Rhodes Scholar at the University of Oxford.

Recently Max was one of eight young people to win the Sustainabilty Leadership Youth A-List which recognises and celebrates the most outstanding professionals in Asia Pacific – people who are pushing for change within their organisations and across policy, business and civil society. The Youth A-List recognises the region’s most impactful sustainable practitioners and leaders aged 30 and below.

Earlier this year he was also chosen as one of National Geographic Society’s 2025 Young Explorers for his work as a climate justice advocate and nonprofit leader from Malaysia mobilising youth for climate action.