From pandas and polar bears to tigers and elephants, iconic animals have long been used to rally public support for nature. But a new international study argues that conservation needs to expand its toolkit — moving beyond charismatic species to embrace a wider range of symbols that can connect people emotionally to the natural world.

Dr Diogo Veríssimo, a researcher at the Environmental Change Institute and co-author of the study, has been at the forefront of applying behavioural science and marketing principles to conservation. His work brings a critical perspective to how campaigns are designed and who they aim to reach. He said:

We want to encourage conservationists to plan their campaigns more like marketers, and select their flagship based on public preferences and cultural values. It is important to bear in mind that the most effective conservation flagships aren’t always the biggest, most colourful or famous animals. What matters more is how well they resonate with specific audiences.”

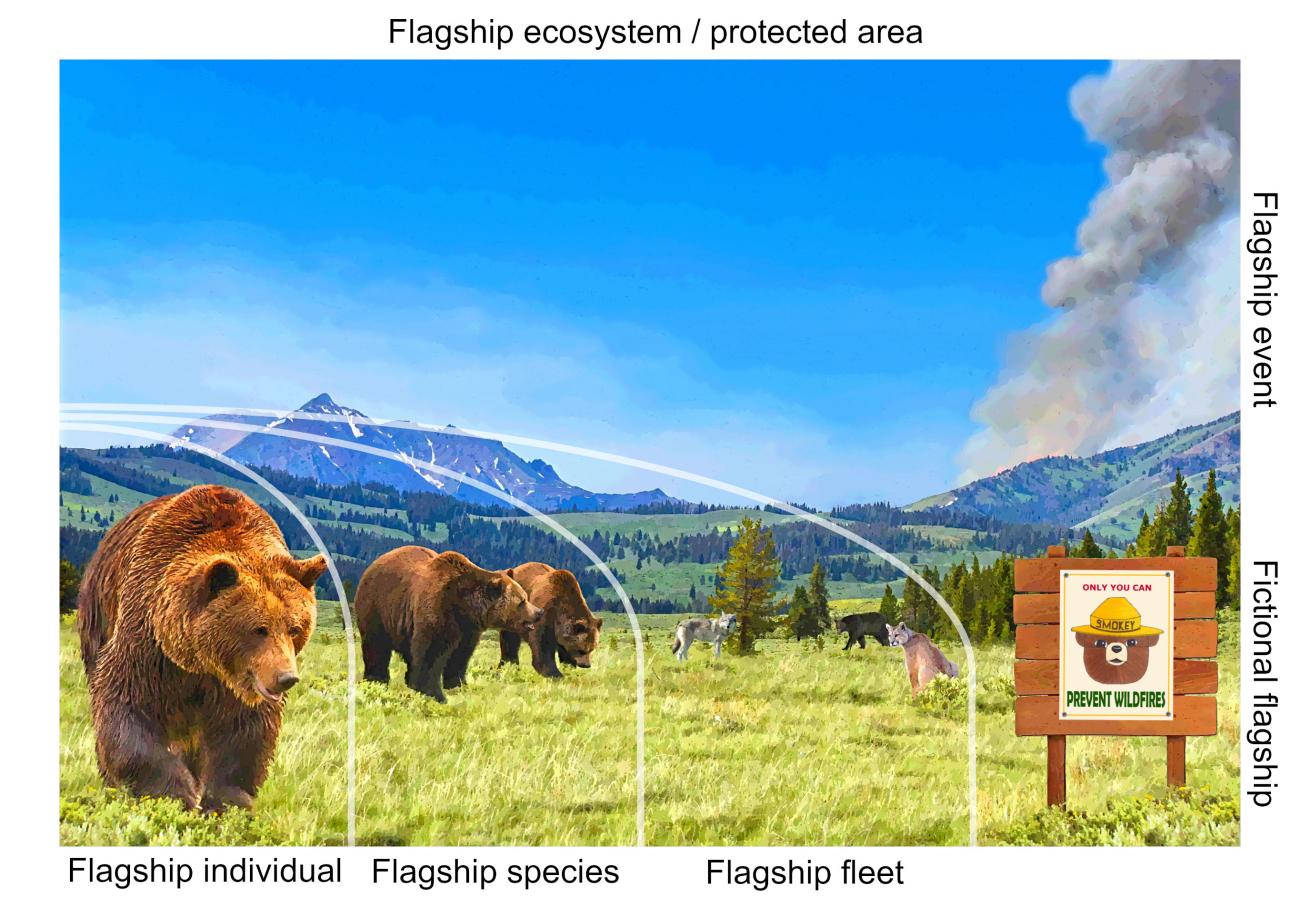

An overview of various flagship categories, with the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem used as an example: Grizzly 399 as a flagship individual – a female grizzly bear, considered the most famous bear in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, attracts huge attention and drives tourism; grizzly bears as a flagship species; large predators, here also including American black bear, wolf, and cougar, as a flagship fleet or flagship community; Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and Yellowstone National Park as a flagship ecosystem or flagship protected area; the wildfire visible in the background represents a flagship event, while the Smokey Bear drawing on the panel sign represents a fictional flagship.

Drawing on experience from conservation campaigns around the world, Dr Veríssimo emphasises the importance of audience-centred strategy. Rather than relying on assumptions, he advocates for evidence-based selection of flagship entities, tailored to the people they aim to engage. He also highlights the need for long-term planning, branding, and measurable impact, urging conservation organisations to evaluate whether their chosen symbols genuinely drive awareness, funding, or behavioural change.

Published in Biological Conservation, the paper introduces the concept of the “flagship entity” — a flexible, inclusive term that goes beyond species to include landscapes, individual organisms, natural events, and even cultural symbols. Whether it’s a coral reef, a lone tortoise, or the spectacular migration of monarch butterflies, anything that evokes emotional engagement can serve as a conservation flagship.

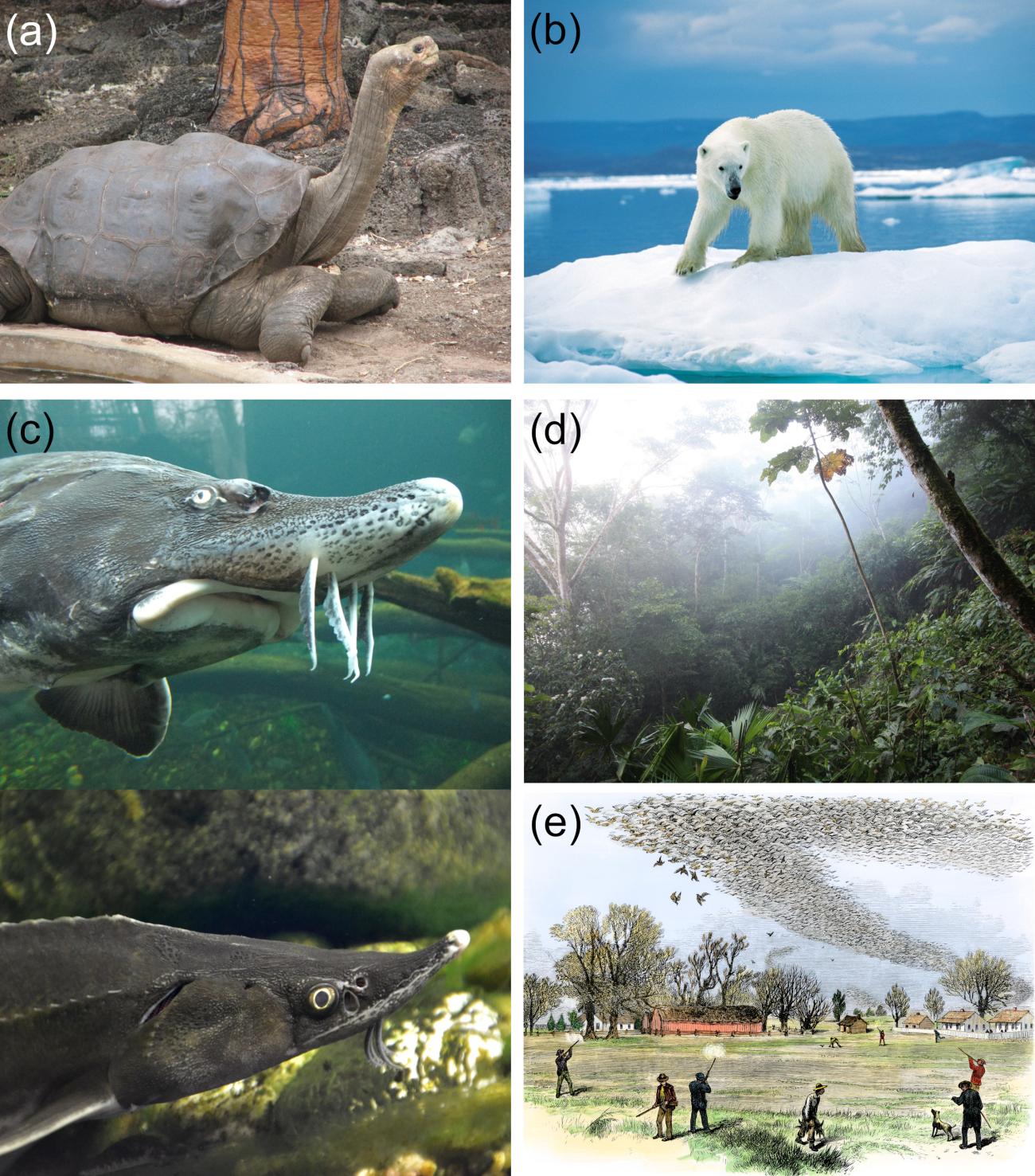

Examples of flagship categories. (a) Flagship individual: Lonesome George, a male Pinta Island tortoise, the last known individual of the subspecies that became widely known as the rarest creature in the world and a symbol of conservation efforts in the Galápagos Islands (photo: Mike Weston; CC BY 2.0); (b) Flagship species: the polar bear, arguably the most iconic symbol of the efforts to mitigate climate change (photo: Ansgar Walk; CC BY 2.5); (c) Flagship fleet: the six Danube sturgeon species, four extant and two extinct in the Danube River, are used as flagships by various conservation organizations; the two species shown here are the beluga (photo: Phyllis Rachler) and sterlet (photo: High Contrast; CC BY 3.0 DE); (d) Flagship ecosystem: the Amazon rainforest is one of the most well-known ecosystems and conservation icons worldwide (photo: Jay; CC BY 2.0); (e) Flagship event: the occurrence of massive flocks of several billions of nowadays extinct passenger pigeons continues to be used as a historic conservation flagship, especially for restoration and rewilding efforts, as well as for de-extinction initiatives (photo: Smith Bennett; public domain).

It also explores how innovative tools such as conservation culturomics — the study of how nature is represented in digital and cultural media — can help identify new and unexpected flagship opportunities. However, the authors caution against unintended consequences such as promoting over-tourism or inadvertently encouraging harmful exploitation. Dr Veríssimo added:

With biodiversity loss accelerating, we need to rethink not just what we protect, but how we communicate its value. This new framework offers a way to broaden conservation appeal and make our messages more inclusive, strategic, and ultimately, more effective.”

The research was led by Ivan Jarić at the University of Paris-Saclay and Czech Academy of Sciences.

Read the full paper in Biological Conservation: A unifying theoretical framework for conservation flagships